poets speak of power

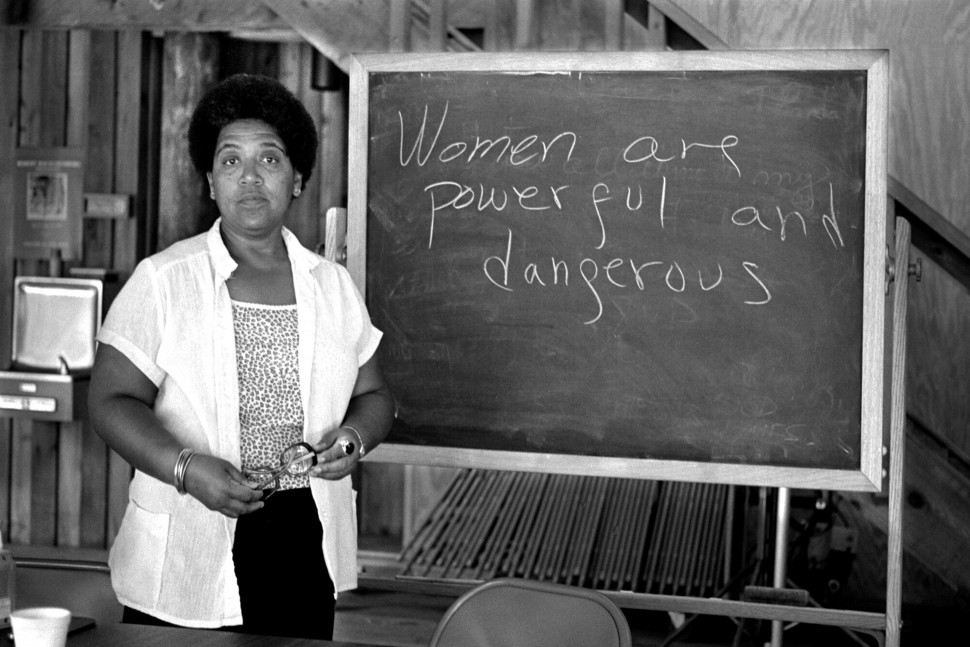

A self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” Audre Lorde dedicated both her life and her creative talent to confronting and addressing the injustices of racism, sexism, and homophobia. Concerned with modern society’s tendency to categorize groups of people, Lorde fought the marginalization of such categories as “lesbian” and “black woman,” empowering her readers to react to the prejudice in their own lives.

Born in New York City of West Indian parents, Lorde came to poetry in her early teens. Her first poem was published by Seventeen magazine when she was still in high school. While Lorde’s love poems composed much of her earliest work, her experiences of civil unrest during the 1960s, along with her sexuality, created a rapid shift to more political statements. As Jerome Brooks reported in Black Women Writers (1950-1980): A Critical Evaluation, “Lorde’s poetry of anger is perhaps her best-known work.” In her poem “The American Cancer Society, or There Is More than One Way to Skin a Coon,” she protested against white America thrusting its unnatural culture on blacks; in “The Brown Menace or Poem to the Survival of Roaches,” she likened blacks to cockroaches, hated, feared, and poisoned by whites. Poetry critic Sandra M. Gilbert remarked that “it’s not surprising that Lorde occasionally seems to be choking on her own anger… [and] when her fury vibrates through taut cables from head to heart to page, Lorde is capable of rare and, paradoxically, loving jeremiads.”

Lorde’s anger did not confine itself to racial injustice but extended to feminist issues as well, and she occasionally criticized African American men for their role in perpetuating sex discrimination: “As Black people, we cannot begin our dialogue by denying the oppressive nature of male privilege,” Lorde stated in Black Women Writers. “And if Black males choose to assume that privilege, for whatever reason, raping, brutalizing, and killing women, then we cannot ignore Black male oppression. One oppression does not justify another.”

Of her poetic beginnings, Lorde commented in Black Women Writers: “I used to speak in poetry. I would read poems, and I would memorize them. People would say, well what do you think, Audre. What happened to you yesterday? And I would recite a poem and somewhere in that poem would be a line or a feeling I would be sharing. In other words, I literally communicated through poetry. And when I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry, and that was when I was twelve or thirteen.”

One of Lorde’s other important themes is the parent-child relationship. In many of Lorde’s poems, the figure of her mother is one of a woman who resents her daughter, tries to repress her child’s unique personality so that she conforms with the rest of the world, and withholds the emotional nourishment of parental love. For example, Lorde tells us in Coal’s “Story Books on a Kitchen Table”: “Out of her womb of pain my mother spat me / into her ill-fitting harness of despair / into her deceits / where anger reconceived me.”

In addition to her poetry, Lorde was noted for eloquent prose, including her courageous account of her agonizing struggle to overcome breast cancer and mastectomy, The Cancer Journals. Her first major prose work, the Journals discuss Lorde confronts the possibility of death. Her Journals also reveal Lorde’s decision not to wear a prosthesis after her breast was removed. Lorde summarized her attitude on the issue thus in the Journals: “Prosthesis offers the empty comfort of ‘Nobody will know the difference.’ But it is that very difference which I wish to affirm, because I have lived it, and survived it, and wish to share that strength with other women. If we are to translate the silence surrounding breast cancer into language and action against this scourge, then the first step is that women with mastectomies must become visible to each other.”

As Allison Kimmich noted in Feminist Writers, “Throughout all of Audre Lorde’s writing, both nonfiction and fiction, a single theme surfaces repeatedly. The black lesbian feminist poet activist reminds her readers that they ignore differences among people at their peril… Instead, Lorde suggests, differences in race or class must serve as a ‘reason for celebration and growth.’”

Power

by Audre Lorde