poets celebrate their own survival

A prolific and widely respected poet, Lucille Clifton’s work emphasizes endurance and strength through adversity, focusing particularly on African-American experience and family life. Awarding the prestigious Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize to Clifton in 2007, the judges remarked that “One always feels the looming humaneness around Lucille Clifton’s poems—it is a moral quality that some poets have and some don’t.”

In addition to the Ruth Lilly prize, Clifton was the first author to have two books of poetry chosen as finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir, 1969-1980 (1987) and Next: New Poems (1987). Her collection Two-Headed Woman (1980) was also a Pulitzer nominee and won the Juniper Prize from the University of Massachusetts. She served as the state of Maryland’s poet laureate from 1974 until 1985, and won the prestigious National Book Award for Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems, 1988-2000 (2000). In addition to her numerous poetry collections, she wrote many children’s books. Clifton was a Distinguished Professor of Humanities at St. Mary’s College of Maryland and a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

Clifton is noted for saying much with few words. In a Christian Century review of Clifton’s work, Peggy Rosenthal commented, “The first thing that strikes us about Lucille Clifton’s poetry is what is missing: capitalization, punctuation, long and plentiful lines. We see a poetry so pared down that its spaces take on substance, become a shaping presence as much as the words themselves” In an American Poetry Review article about Clifton’s work, Robin Becker commented on Clifton’s lean style: “Clifton’s poetics of understatement—no capitalization, few strong stresses per line, many poems totaling fewer than twenty lines, the sharp rhetorical question—includes the essential only.”

Clifton’s first volume of poetry, Good Times (1969), was cited by the New York Times as one of the ten best books of the year. The poems, inspired by Clifton’s family of six young children, show the beginnings of Clifton’s spare, unadorned style and center around the facts of African-American urban life. Clifton’s second volume of poetry, Good News about the Earth: New Poems(1972), was written in the midst of the political and social upheavals of the late 1960s and 70s, and its poems reflect those changes, including a middle sequence that pays homage to black political leaders. Writing in Poetry, Ralph J. Mills, Jr., said that Clifton’s poetic scope transcends the black experience “to embrace the entire world, human and non-human, in the deep affirmation she makes in the teeth of negative evidence.”

However, An Ordinary Woman(1974), Clifton’s third collection of poems, largely abandoned the examination of racial issues that had marked her previous books, looking instead at the writer’s roles as woman and poet. Helen Vendler declared in the New York Times Book Review that Clifton “recalls for us those bare places we have all waited as ‘ordinary women,’ with no choices but yes or no, no art, no grace, no words, no reprieve.” Generations: A Memoir (1976) is an “eloquent eulogy of [Clifton’s] parents,” Reynolds Price wrote in the New York Times Book Review, adding that, “as with most elegists, her purpose is perpetuation and celebration, not judgment…There is no sustained chronological narrative. Instead, clusters of brief anecdotes gather round two poles, the deaths of father and mother.” The book was later collected in Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir: 1969-1980, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize along with Next: New Poems (1987).

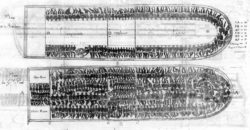

The book that followed Clifton’s dual Pulitzer nomination, Quilting: Poems 1987-1990 (1991), also won widespread critical acclaim Using a quilt as a poetic metaphor for life, each poem is a story, bound together through history and figuratively sewn with the thread of experience. Each section of the book is divided by a conventional quilt design name—”Eight-pointed Star” and “Tree of Life”—which provides a framework for Clifton’s poetic quilt. Clifton’s main focus is on women’s history; however, according to Robert Mitchell in American Book Review, her poetry has a far broader range: “Her heroes include nameless slaves buried on old plantations, Hector Peterson (the first child killed in the Soweto riot), Fannie Lou Hamer (founder of the Mississippi Peace and Freedom Party), Nelson and Winnie Mandela, W. E. B. DuBois, Huey P. Newton, and many other people who gave their lives to [free] black people from slavery and prejudice.”

Speaking to Michael S. Glaser during an interview for the Antioch Review, Clifton reflected that she continues to write, because “writing is a way of continuing to hope … perhaps for me it is a way of remembering I am not alone.” How would Clifton like to be remembered? “I would like to be seen as a woman whose roots go back to Africa, who tried to honor being human. My inclination is to try to help.”